We need to improve the accuracy of AI accuracy discussions

Reading the tech press, you would be forgiven for believing that AI is going to eat pretty much every industry and job. Not a day goes by without another reporter breathlessly reporting some new machine learning product that is going to trounce human intelligence. That surfeit of enthusiasm doesn’t originate just with journalists though — they are merely channeling the wild optimism of researchers and startup founders alike.

There has been an explosion of interest in artificial intelligence and machine learning over the past few years, as the hype around deep learning and other techniques has increased. Tens of thousands of research papers in AI are published yearly, and AngelList’s startup directory for AI companies includes more than four thousands startups.

After being battered by story after story of AI’s coming domination — the singularity, if you will — it shouldn’t be surprising that 58% of Americans today are worried about losing their jobs to “new technology” like automation and artificial intelligence according to a newly released Northeastern University / Gallup poll. That fear outranks immigration and outsourcing by a large factor.

The truth though is much more complicated. Experts are increasingly recognizing that the “accuracy” of artificial intelligence is overstated. Furthermore, the accuracy numbers reported in the popular press are often misleading, and a more nuanced evaluation of the data would show that many AI applications have much more limited capabilities than we have been led to believe. Humans may indeed end up losing their jobs to AI, but there is a much longer road to go.

Another replication crisis

For the past decade or so, there has been a boiling controversy in research circles over what has been dubbed the “replication crisis” — the inability of researchers to duplicate the results of key papers in fields as diverse as psychology and oncology. Some studies have even put the number of failed replications at more than half of all papers.

The causes for this crisis are numerous. Researchers face a “publish or perish” situation where they need positive results in order to continue their work. Journals want splashy results to get more readers, and “p-hacking” has allowed researchers to get better results by massaging statistics in their favor.

Artificial intelligence research is not immune to such structural factors, and in fact, may even be worse given the incredible surge of excitement around AI, which has pushed researchers to find the most novel advances and share them as quickly and as widely as possible.

Now, there are growing concerns that the most important results in AI research are hard if not impossible to replicate. One challenge is that many AI papers are missing the key data required to run their underlying algorithms or worse, don’t even include the source code for the algorithm under study. The training data used in machine learning is a huge part of the success of an algorithm’s results, so without that data, it is nearly impossible to determine whether a particular algorithm is functioning as described.

Worse, in the rush to publish novel and new results, there has been less focus on replicating studies to show how repeatable different results are. From the MIT Technology Review article linked above, “…Peter Henderson, a computer scientist at McGill University in Montreal, showed that the performance of AIs designed to learn by trial and error is highly sensitive not only to the exact code used, but also to the random numbers generated to kick off training, and to ‘hyperparameters’—settings that are not core to the algorithm but that affect how quickly it learns.” Very small changes could lead to vastly different results.

Much as a single study in nutrition science should always be taken with a grain of salt (or perhaps butter now, or was it sugar?), new AI papers and services should be treated with a similar level of skepticism. A single paper or service demonstrating a singular result does not prove accuracy. Often, it means that a very choice dataset operating with very specific conditions can lead to a high point of accuracy that won’t apply to a more general set of inputs.

Accurately reporting accuracy

There is a palpable excitement about the potential of AI to solve problems as diverse as clinical evaluation at a hospital to document scanning to terrorism prevention. That excitement though has clouded the ability of journalists and even researchers from accurately reporting accuracy.

Take this recent article about using AI to detect colorectal cancer. The article says that “The results were impressive — an accuracy of 86 percent — as the numbers were obtained by assessing patients whose colorectal polyp pathology was already diagnosed.” The article also included the key results paragraph from the original study.

Or take this article about Google’s machine learning service to perform language translation. “In some cases, Google says its GNMT system is even approaching human-level translation accuracy. That near-parity is restricted to transitions between related languages, like from English to Spanish and French.”

These are randomly chosen articles, but there are hundreds of others that breathlessly report the latest AI advances and throw out either a single accuracy number, or a metaphor such as “human-level.” If only evaluating AI programs were so simple!

Let’s say you want to determine whether a mole on a person’s skin is cancerous. This is what is known as a binary classification problem — the goal is to separate out patients into two groups: people who have cancer, and people who do not. A perfect algorithm with perfect accuracy would identify every person with cancer as having cancer, and would identify every person with no cancer as not having cancer. In other words, the results would have no false positives or false negatives.

That’s simple enough, but the challenge is that conditions like cancer are essentially impossible to identify with perfect accuracy for computers and humans alike. Every medical diagnostic test usually has to make a tradeoff between how sensitive it is (how many positives does it identify correctly) versus how specific it is (how many negatives does it identify correctly). Given the danger of misidentifying a cancer patient (which could lead to death), tests are generally designed to ensure a high sensitivity by decreasing specificity (i.e. increasing false positives to ensure that as many positives are identified).

Product designers have choices here in how they want to balance those competing priorities. The same algorithm might be implemented differently depending on the the cost of false positives and negatives. If a research article or service doesn’t discuss these tradeoffs, then accuracy is not being fairly represented.

Even more importantly, the singular value of accuracy is a bit of a misnomer. Accuracy reflects how many positive patients were identified positively and how many negative patients were identified negatively. But we can maintain the same accuracy by increasing one number and decreasing the other number or vice versa. In other words, a test could emphasize detecting positive patients well, or it could emphasize excluding negative patients from the results, while maintaining the same accuracy. Those are very different end goals, and some algorithms may be better tuned toward one rather than the other.

That’s the complication of using a single number. Metaphors are even worse. “Human-level” doesn’t say anything — there is rarely good data on the error rate of humans, and even when there is such data, it is often hard to compare the types of errors made by humans versus those made by machine learning.

That’s just some of the complications for the simplest classification problem. All of the nuances around evaluating AI quality would take at least a book, and indeed, some researchers will no doubt spend their entire lives evaluating these systems.

Everyone can’t get a PhD in artificial intelligence, but the onus is on each of us as consumers of these new technologies to apply a critical eye to these sunny claims and rigorously evaluate them. Whether it is reproducibility or breathless accuracy claims, it is important to remember that many of the AI techniques we rely on are mere technological babies, and still need a lot more time to mature.

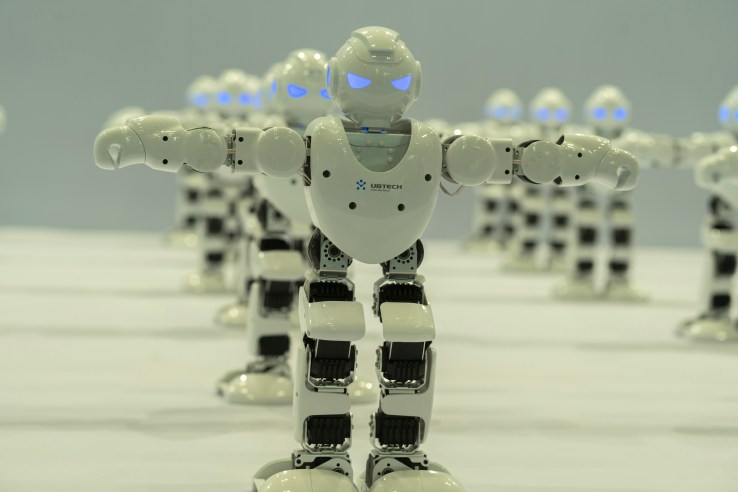

Featured Image: Zhang Peng/LightRocket/Getty Images