Using drones to build the ambulance fleet of the future

It’s that time of year again. Sleigh bells overhead and our jolly, bearded benefactor wafting gifts down the chimney to eagerly awaiting hands. We’ve heard every version of this tale. Except, perhaps, the variant that is currently playing out in East Africa. In the funny way that magic tales and science fiction sometimes become reality, if you swap out sleigh bells for drones and gifts for emergency medical supplies, you’ve got the real world tale of Zipline, a company delivering 20% of national blood supply via drone in Rwanda. The Sequoia and A16Z-backed company recently announced it would be expanding operations to neighboring Tanzania.

Meanwhile, here in the U.S. the drone sleigh bells are few and far between, hampered by our aviation regulatory framework, which has not kept pace. In October the Trump Administration signed an executive order giving local governments more leeway to conduct unmanned drone tests. The order allows local governments and communities to work with industry to design their own trial programs and apply to the Federal Aviation Administration for waivers to the existing rules. “Our nation will move faster, fly higher, and soar proudly toward the next great chapter of American aviation” said Trump. The direction was the right one. But there has been little follow up and the rate of progress remains lightyears behind other countries, prompting Amazon and Google to head overseas to the UK and Australia to conduct drone tests the past few years.

In an interview for Flux podcast I sat down with Keller Rinaudo, the CEO of Zipline, for a wide-ranging conversation about government policy, innovation and the future of autonomous infrastructure. We got into how he thinks the U.S. government has become ossified and what it would take to become a leader in this space. He also shares how he’s built a successful partnership with UPS, dealt with naysayers, and how he thinks about risk. At the heart of the Zipline story is real-world grit, a dedicated team, cutting-edge technology, and a government bold enough to take risks. An excerpt of the conversation is published below.

Let’s start with a quick overview of what Zipline is doing. Essentially instant delivery for life-saving healthcare?

KR: That’s a great explanation. Zipline is looking to build instant delivery for the planet and our mission is to deliver urgent medical products to people in difficult to reach and remote places. Today we’re operating at national scale in Rwanda. We’re delivering a significant percentage of the national blood supply on a day to day basis and we allow hospitals across the country to get instant access to any blood product that a patient needs on either a routine or an emergency basis.

AMLG: I read that by this past summer of 2017 you’d climbed to 20 deliveries per facility per week, is that right?

KR: That sounds right on average. It depends on the size of the hospital. There are certain hospitals that are smaller and hospitals that are larger but around 20 deliveries per hospital per week. The most important thing to realize is the hospitals we serve, they only receive blood deliveries via the Zipline system and most of them are receiving multiple deliveries a day.

AMLG: So you’ve built seven of 21 planned facilities in Rwanda which is your first market right?

KR: We’re actually at eight. That number is changing as we’re adding hospitals to the system every day. In the long run our goal is to be serving all healthcare facilities across Rwanda. Something like 40 hospitals. Then there are an additional 400 health centers that don’t do blood transfusions but do need access to a whole host of medical products that are hard to get access to. In the long run the vision of the Rwandan government is to put each of their 13 million citizens within a 15 minute delivery of any essential medical product they could need.

AMLG: In terms of how it works — the staff in these clinics, they text a distribution center where the workers pack the medications into a box that they then load it into the Zip. Then it takes off and goes and airdrops the payload and returns to the distribution center without having landed at all?

KR: Yeah. Although sometimes what we do sounds a bit weird or like science fiction, people who come and see it are always shocked by the simplicity of it. The surprising thing about this system particularly when you’re talking to doctors who are using it on a day to day basis, it’s so simple. It’s like sending a text message and then instantly receiving the product that you needed to treat a patient or even save a patient’s life. We’re doing that using autonomous electric vehicles. They weigh about 13 kilograms. They fly at about 100 kilometers an hour. There’s really no human involved during the delivery of it. From the moment the vehicle leaves our distribution center to the moment it returns, it’s making all of its own decisions. It’s flying itself to the hospital delivering the product and then returning home. When we deliver it’s important to know we don’t land the plane. The plane is essentially coming within 30 feet of the ground and then dropping the payload in — we call it an air brake — you can kind of think it as a simple cost-effective parachute that ensures that the package falls right on the doorstep of the hospital in a gentle magical way.

AMLG: I’ve watched the video — it looks like a little red shoe box. So you fill it with sachets of blood and there’s a QR code so the vehicle automatically knows exactly where to go. Then it parachutes down in a gentle, magical way?

KR: Yes and you can actually catch the package. If they’re standing out there a lot of times they’ll catch the package because it’s so precise. We can deliver into about two to three parking spaces. The experience for the user is bit like using a ride sharing service — you’re indicating that you need something. You’re getting a text message back saying “Thanks for the order. Zip has been dispatched. It’s 12 minutes away.” Then you get a second text message saying “Zips one minute away please walk outside to receive the package.” That’s it. You do not need anything other than a cell phone to place an order and get an instant delivery of a product needed to treat a patient. There is no infrastructure required, very little training, anybody can use it.

AMLG: It’s probably more reliable than my Uber turning up where I think it’s going to turn up at the time I think it’s going to turn up. Because there’s no humans in the loop unless something goes wrong, right?

KR: There is a human in the loop in the sense that we have an air traffic controller that is in communication with the vehicles at all times and can issue high level commands to different vehicles in the fleet if necessary. But those cases of intervention are exceedingly rare. The vast majority of the time these vehicles make their own decisions, monitor their own health, successfully complete missions and return to the distribution center.

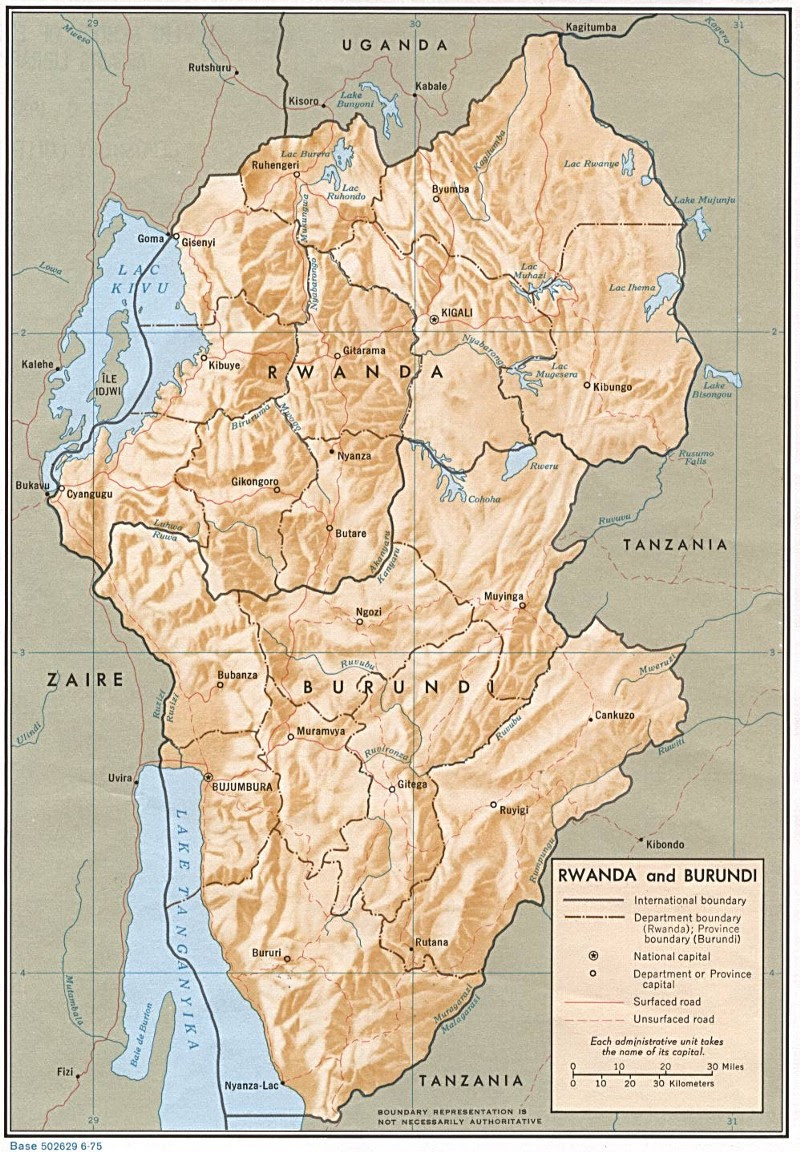

Rwanda is located in East Africa, and mountains dominate the central and western parts of the country.

AMLG: In terms of Rwanda — its a pretty wild, mountainous country. What did you have to do technically to support the navigation system, did you just use 3D satellite maps and pair these with manual ground surveys, or what?

KR: One of the characteristics of Rwanda that made it a good place to start with this technology is that it’s a mountainous country. It’s known as the Land of a Thousand Hills. It can often take, by nature of that topography, a long time. Roads tend to be windy. We actually took open source topographical maps of the country and then loaded those — along with more precise 3D surveys of the delivery sites that we serve — we loaded those both into the navigation system of the airplanes so that when you have a package the vehicle is scanning the barcode of that package and then instantly has its mission. It knows where it needs to go and there’s no programming in coordinates. That’s all done ahead of time because each path is predesignated from the distribution centre to a hospital we serve. Every time you’re doing a delivery to that hospital the plane is flying in the exact same path. This is how we ensure that the system operates in a predictable, reliable, ultimately boring way. Logistics should be boring. There shouldn’t be any surprises.

AMLG: What about the design process, what didn’t you expect — were there breakthroughs in how you designed the system to be this efficient and this simple? Was the aircraft catching method where you hook it on landing what you decided to do from the get go?

KR: When we were getting started this had never been done before. It still has not been done by anyone else in the world. We had no idea if it would work. Some of the more intricate parts of the system — the way we recover the airplanes for example — the airplane doesn’t have any landing gear and we don’t have runways.

A Zip being snatched out of the sky, with onlookers observing the “sky ambulance”

Recovering the plane from 100 kilometers an hour, snatching it out of the air and gently bringing it to a halt is an exceedingly tricky problem. The solutions that we initially tried, we were shocked that some of them worked as well as they did. On the technology side there was always doubt in the back of our minds about whether this was even possible. When we were building it everybody was telling us it wasn’t possible and that can mess with your head.

AMLG: On the technological side or business side?

KR: On every side. The overwhelming advice we got was, this is not technologically possible. Even if it were technologically possible it wouldn’t work reliably. Even if it did work reliably there’s no willingness to pay for it and no need for it in different parts of the world. Even if there were a need for it the technology won’t be able to operate at scale. Over the course of the last three years every year we’ve had to disprove one of those notions. Now I think they are all disproved. But even now people who look at what we’re doing will say, well OK the technology works and it works reliably and it works at scale and it turns out there is a need for it, but only in that country that you’re in. It won’t apply to other countries. That’s the next mistaken notion that we’re working on correcting now.

But in terms of being surprised, whenever you’re trying to do something for the first time in the world there’s a lot of uncertainty from a technology perspective. That first time that you see something that you build work is always miraculous and surprising. The other surprising thing to us is that we knew this was going to look weird. Having an autonomous electric vehicle delivering urgent medical products from the sky in a remote part of Rwanda, that looks kind of crazy.

AMLG: Looks crazy to the locals?

KR: Yeah. We do a survey flight to the hospital before we begin delivering medical products, just to make sure that the route is working perfectly and the numbers look good. And the doctor there was telling me they were having problems because all the patients were climbing out of bed to see the vehicle as it was coming by. The doctors were trying to keep the patients in the beds because it wasn’t good for them to be getting out of bed.

AMLG: Unintended consequences!

KR: Exactly. There is an element of this that is radically different. There’s a magic or science fiction to it. But the surprising thing to me was that after seven days all of the magic and science fiction is gone and the doctors treat this as the most obvious thing in the world. They expect the service, they rely on it and they find it boring. It’s amazing how fast you go from science fiction to this is just the way we do it.

A Zip drops medical supplies at a local health facility

AMLG: You make it look easy but I know how much resistance there is on many fronts to get to this, it’s remarkable. One of my favorite things you’ve said is that the locals call it the “sky ambulance” — it’s obvious, the sky ambulance is coming.

KR: It’s like, of course.

AMLG: In terms of the technological breakthrough — you’re building the drones yourself, you’re designing manufacturing and operating a completely new fleet of vehicles every four to five months. You’re borrowing a lot from existing flight control systems and best practice in the aerospace industry, but how is that rapid iteration working? What kind of changes do you make every four to five months?

KR: Zipline designs the flight computer, which means that we are actually designing the boards and the microprocessors that are making decisions on board the vehicle. We’re designing the overall avionics system. We design the flight controls, which is the math that allows the vehicle to fly. We design the guidance and navigation system, which is how the plane finds its way out to where it needs to go. We also design the air traffic control algorithms and the communication architecture of the plane. We design the airframe and we design the entire distribution centre that needs to be able to launch and recover these planes at high volume on a daily basis in a reliable way. By owning the full stack — one thing most people don’t realize about Boeing is that Boeing is only a final integrator, and when you go and try to build a plane like the 787 it’s this complicated rats nest of subcontractors subcontracting to subcontractors, and that leads to projects being expensive and slow.

But when one small team of hardworking engineers can own the entire system from scratch you can move fast. If something’s going wrong you just turn to your right and say, hey so-and-so you built this system, we need to change it by this afternoon. The other thing that we’ve done that’s enabled the speed of the company is we do all of our engineering, manufacturing and flight operations in the same place. When you step outside there are planes flying. So if a plane looks like it’s not flying right or a component you designed looks like it’s not working the right way, you can design something different, run into the manufacturing shop, get something built in a different way and then test it that day. The rate of iteration is 100 times faster than in a traditional aerospace company.

AMLG: It reminds me of SpaceX and how they rethought the operations and the layout of the engineering floor so they could have that quick communication loop.

KR: A significant portion of our engineering team is from SpaceX and we have learned a vast amount from how SpaceX designed those rockets. It’s quite difficult to design aerospace systems quickly but also in a safe way. Those two goals are in tension with one another. SpaceX has led the way in terms of showing how that’s possible and now we’re trying to show that it’s possible with airplanes not just rockets.

AMLG: How big is your team now?

KR: We have something like 60 people full-time.

AMLG: How do you keep that number capped as you expand the business to other countries and other use cases?

KR: We won’t keep it capped as we expand into new countries. One of the most important things to understand about what’s happening in Rwanda right now is that distribution center is being led by an extraordinary team of full-time Zipline employees, but they are also native Rwandans. The technical lead at that distribution center is an extraordinary engineer named Abdul. The rest of the team are hardworking, super smart, and driven to make sure that the system has a positive impact on patient health, which is our mission.

Each country we go into we hire a full team of people to run the distribution centers in that country. That team is not U.S. expats, they’re predominantly citizens of the country we’re launching in. That said from a headquarters perspective we focus on hiring people who love taking on huge hairy technical problems who can do the work of 30 or 40 engineers at a place like Boeing. That’s the only thing a startup can do to survive in this space. You can’t spend $32 billion dollars developing an airplane like Boeing did with the 787. You have to figure out a way of doing that for five or six orders of magnitude less.

AMLG: The lean aerospace startup.

KR: Exactly. That means people have to own more, move faster, be willing to take risk. And — although this sounds crazy in an aerospace startup — especially under test conditions you have to be willing to crash. If you’re not willing to crash then you’re in this regime of ultra risk aversion that will prevent you from ever doing anything new.

AMLG: Have you had any planes crash since you’ve started operating? I presume it has to happen.

KR: One of the big learnings for us from the testing we were doing in Half Moon Bay at our offices was it was important to design an ultimate failsafe into the system. If every other component and safety mechanism on the plane fails you must be able to ensure that the plane is going to come to the ground in a safe and reliable way. So we actually designed a parachute into the plane. It works much like the Cirrus, a high end general aviation aircraft that you can buy today. The Cirrus has a similar system where you have a ballistically deployed parachute. We’ve designed a simpler system into our airplanes such that if all the other safety components of the vehicle fail the plane can pull its parachute and come to the ground so gently that you can catch it. We use that commonly under test circumstances at our headquarters. It’s a good thing we built it because we have experienced significant anomalies, things that we weren’t expecting having to do with the fact that Rwanda is a different environment than the environment we were testing in.

AMLG: Lets get into the economics — you’ve said the business has been profitable from day one and that the costs will come down as you continue to improve the supply chain and as volume goes up. Can you speak to the unit economics and how they will change as you expand?

KR: One of the exciting things about working with the Rwandan government is they think about projects like this differently. A lot of places in the developing world have an attitude of, we want this for free or we want it to be done by a non-profit or we want it to be philanthropy. The Rwandan government’s approach is different. You always hear the president of Rwanda talking about trade not aid.

AMLG: I think there’s a misconception that you’re doing philanthropy, but you’re not — you’re making money on these deliveries right?

With the rapid adoption of mobile phones, many Africans have bypassed state-owned phone companies and banks in favor of mobile payments. 10 year old company M-Pesa, a service that lets you send money via cellphone, now has over 30 million users. M-Pesa processed ~6 billion transactions in 2016. [Source]

KR: Yes that’s important. We don’t make a lot of money on the deliveries, it’s not a high margin business. But it is important to understand that philanthropy doesn’t scale. Sustainable profitable businesses do scale. The best example of this are cellphone networks in Africa and how absolutely transformative that business model has been for everybody’s lives across the continent.

We want to show that it’s possible to use this kind of technology to similarly leapfrog. In the same way that cellphones allowed many countries to leapfrog the absence of landlines we think this kind of technology can show that it’s possible to leapfrog the absence of roads or low quality roads to make fast deliveries in a highly cost-effective way. It’s important to show that this is sustainable and that is the key thing. This is not some philanthropic thing that’s going to go on for a year and when the funding dries up it’s done. This can support itself. It’s economically viable and it can fund future growth both in Rwanda and in other countries across the world.

AMLG: It seems that Rwanda has been a great initial test bed. As you look at other countries in the developing world, a lot of local governments are tied closely to the business community, there’s corruption, bureaucracy, long sales cycles. How do you evaluate which markets you’re going to go into?

KR: There was a reason that we chose Rwanda first. The government there is extraordinarily disciplined. They make decisions fast and they’re investing heavily in healthcare and technology. As a U.S. citizen I wish our country could make decisions that quickly and that responsibly. I assure you we can’t.

AMLG: You’ve said its bittersweet that you’re having to start in Africa and that you couldn’t do this right away in the U.S.?

KR: Well at this point I consider myself at least an honorary Rwandan. The people of that country are so incredibly deserving and hardworking. The level of ambition of a country that has limited resources relative to a country like the U.S., to say we don’t just want to have the best healthcare system in East Africa, we don’t just want to have the best healthcare system in the developing world, why don’t we just go build one of the best healthcare systems in the world and let’s use technology and robotics and artificial intelligence to get there. That’s extraordinary. But yeah it is bittersweet. We’re a U.S. company and the reality is that the same positive impact that this system is having in Rwanda, it could have that same positive impact on patient health in the U.S. There are people who live in remote parts of this country who don’t have the same access to healthcare that you have if you’re living in a city or on the coasts. That’s a shame. We’re essentially waiting for the U.S. government to catch up to a country like Rwanda, in terms of using technology to make people’s lives better.

AMLG: Right. As you said it’s probably a lot about attitudes as well — it takes a special culture and government to say we are going to be first, we’re going to lead. And the U.S. in this case wants to be first to be second and have it proved out perhaps. I know the FAA’s line of sight restrictions still in place but they do relax regulations for certain companies in certain areas to test out. You made a recent announcement with the White House about doing tests in the U.S. — the Navajo reservation delivery or Smith Island in D.C.? Can you talk about those?

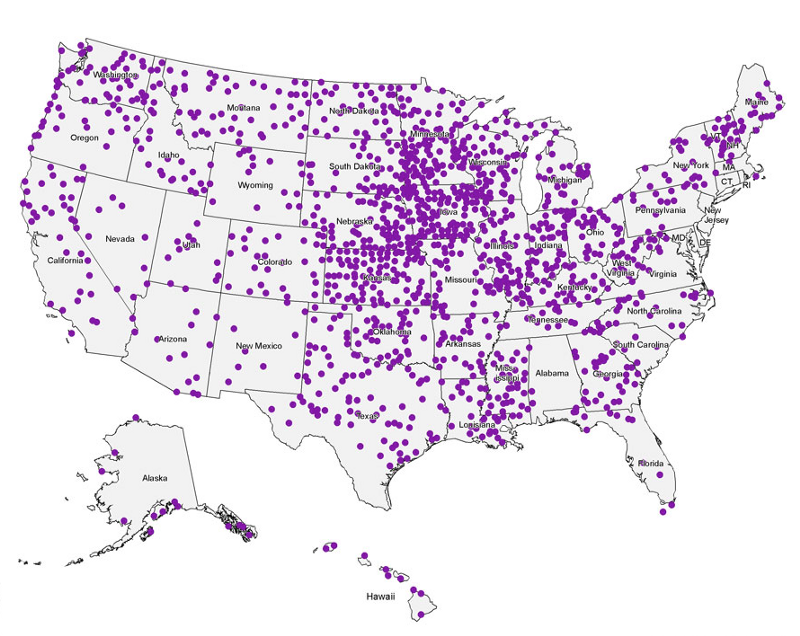

KR: As I mentioned there are these places where you can actually look at the data — people who live in rural places in the U.S. have worse health outcomes than people who live in urban cities. A big part of that has to do with access. If you live 150 miles from the nearest hospital and you have a medical emergency the chances of you surviving are worse. It’s not that surprising. Particularly in places in the U.S. where the roads might not be good or where you are remote or where you have Critical Access Hospitals or clinics that may be stocking out of products or may only hold a small number of medical products on hand and not the ones you might need, having instant delivery is an obvious idea. One thing that blows my mind is that we have instant delivery for hamburgers but we don’t have instant delivery for medicine. That makes no sense.

AMLG: The U.S. has certain priorities, burgers are a matter of national pride…

KR: Haha. But the fact that the fast food industry is out-innovating the medical industry is a scary sign of how slow the medical industry is moving. That said, because we’re working closely with the government and with the FAA, we know that the FAA is pushing hard. Everybody does want to encourage this industry. We don’t want the U.S. to fall behind in terms of core infrastructure projects of the future. That said the FAA needs data. So we are now generating as much data as we can to allow regulators across the world to become more and more comfortable and essentially to understand that this is inevitable.

AMLG: It’s a bit like autonomous cars, where they’re collecting tons of data to show the safety of their vehicles on the road. So you are porting all this data that you are currently documenting to be able to come to the U.S., right?

KR: We’re not overly focused on the U.S. The reality is that we’re an international company. There are so many countries all of which have different healthcare systems and so in each case the need is a bit different. As with any new technology or innovation, there are unknowns around what are the effects, how do you regulate it, how do you manage it. That’s true for everything. The reality is that the most innovative disciplined countries out there are going to be the ones that seize the opportunity first. Of course the countries that seize the opportunity first, that used to be the U.S. The U.S. led the way in aviation for the first half of the 20th century. But it may be different countries in the future. Those countries that lead the way are the ones that reap the outsized benefits of that technology because they’re usually the ones that own the manufacturing base and the innovation base for that technology into the future.

AMLG: I do want to talk hypothetically at least about the U.S. market and specifically the healthcare market. From what I’ve read it seems like there’s two things. One is what you’ve sort of outlined, which is the rural use cases, there’s a high rural population in the U.S. so that makes sense. The other would be things around personalized medicine, so rare immunotherapies, cell gene therapies, biologics that require temperature control, humidity control and monitoring of the shipments while they’re moving through the supply chain. As you’ve talked to health networks and pharmacies in the U.S. What have you found about their response? The U.S. healthcare system is notoriously bureaucratic and it’s one of the glaring areas where there’s been no innovation and people have tried time and time again to crack it. How in theory could you crack innovation and the U.S. healthcare market?

KR: I think it has to come from the doctors. A bureaucrat in a regulatory agency having to do with healthcare in the U.S. is going to give you one answer. But a month ago I gave a presentation in front of about 1000 doctors in the U.S. and was absolutely mobbed after the conversation. All I’m doing is saying, here’s what we’re doing in Rwanda. And doctors are saying “wow, here is how I would use this. I just had this case the other day where I could have used instant delivery.”

AMLG: So I have to ask, doctors have a lot of pain points in their business and they’ve wanted change in the system, but pharmacies, hospitals insurance companies, PBMs — there’s a lot of legacy interests there that people haven’t been able to crack through. You can have the enthusiasm from doctors but it hasn’t really worked for other businesses who are trying to change the system. What could you do differently? Could you take advantage of existing supply chains, how could you integrate there, how could you serve hospitals? What’s the wedge?

KR: There are lots of ways. There are lots of healthcare logistics companies in the U.S. For instance UPS has a large healthcare logistics branch. There are companies that specialize in this — McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health. These are some of the biggest companies that nobody has ever heard of. They are huge, and hugely complex systems that are designed to deliver medicine to health centers and hospitals across the country. The way that you start is you focus on urgent and emergency medical products and you make it clear that if a patient is dying the doctor can get the product they need to say that patients life.

It’s a very simple idea. Even the bureaucracy of the healthcare system is not going to be sufficient to prevent someone someone who is dying or someone’s family from using that system or insisting that it be used. The reality is that in our conversations with those healthcare logistics companies in the U.S., they’re super innovation-forward because their desire is to provide the highest level of service to the hospitals and health centers that they deliver medical products to. So it’s actually not that complicated. It’s not like you’re trying to get a new medical compound. You’re just saying, hey this is 10 to 20 times as fast. So if you need a medical product quickly you can get it.

AMLG: And it basically needs to be cheaper than a helicopter which is how emergency supplies get delivered?

KR: Yes. A pretty low bar. We can be conceivably a hundred to a thousand times less expensive than a helicopter.

KR: I think it has to come from the doctors. A bureaucrat in a regulatory agency having to do with healthcare in the U.S. is going to give you one answer. But a month ago I gave a presentation in front of about 1000 doctors in the U.S. and was absolutely mobbed after the conversation. All I’m doing is saying, here’s what we’re doing in Rwanda. And doctors are saying “wow, here is how I would use this. I just had this case the other day where I could have used instant delivery.”

AMLG: So I have to ask, doctors have a lot of pain points in their business and they’ve wanted change in the system, but pharmacies, hospitals insurance companies, PBMs — there’s a lot of legacy interests there that people haven’t been able to crack through. You can have the enthusiasm from doctors but it hasn’t really worked for other businesses who are trying to change the system. What could you do differently? Could you take advantage of existing supply chains, how could you integrate there, how could you serve hospitals? What’s the wedge?

KR: There are lots of ways. There are lots of healthcare logistics companies in the U.S. For instance UPS has a large healthcare logistics branch. There are companies that specialize in this — McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health. These are some of the biggest companies that nobody has ever heard of. They are huge, and hugely complex systems that are designed to deliver medicine to health centers and hospitals across the country. The way that you start is you focus on urgent and emergency medical products and you make it clear that if a patient is dying the doctor can get the product they need to say that patients life.

It’s a very simple idea. Even the bureaucracy of the healthcare system is not going to be sufficient to prevent someone someone who is dying or someone’s family from using that system or insisting that it be used. The reality is that in our conversations with those healthcare logistics companies in the U.S., they’re super innovation-forward because their desire is to provide the highest level of service to the hospitals and health centers that they deliver medical products to. So it’s actually not that complicated. It’s not like you’re trying to get a new medical compound. You’re just saying, hey this is 10 to 20 times as fast. So if you need a medical product quickly you can get it.

AMLG: And it basically needs to be cheaper than a helicopter which is how emergency supplies get delivered?

KR: Yes. A pretty low bar. We can be conceivably a hundred to a thousand times less expensive than a helicopter.

AMLG: In terms of how you would get to scale in the U.S. — there’s about 6,000 hospitals. How many of these distribution centers would you need to cover the U.S.?

KR: I think that with about 20 distribution centers you could cover 70 to 80 percent of the U.S. population. When you think about that that’s incredible scale. Because each distribution center is a relatively low fixed cost. We can set it up in two weeks. You could build an instant delivery network for the entire country in six to eight months if the regulatory regime were amenable to it.