Where venture capital has peaked

“Peak startup” is a phrase that no doubt strikes terror in the hearts of entrepreneurs and startup investors alike.

But saying “peak startup” is not the same as saying that the market is at the very height of a bubble. Indeed, with SoftBank driving late-stage valuations to the chagrin of IPOs, worldwide early and late-stage rounds growing in size and U.S. venture market’s stabilizing, we are not seeing the imminent implosion of the market for private equity.

Peak startup merely means that the market is running out of steam for this cycle. Despite the fact that deal and dollar volume are at or near post-dot-com bubble highs globally, there’s a chance — at least for this cycle — the U.S. startup market’s best days are behind it. And that’s what we’re going to examine here: a quantitative and qualitative case arguing that peak startup has come and gone in America.

The tarnished star of Texas VC prompts a question

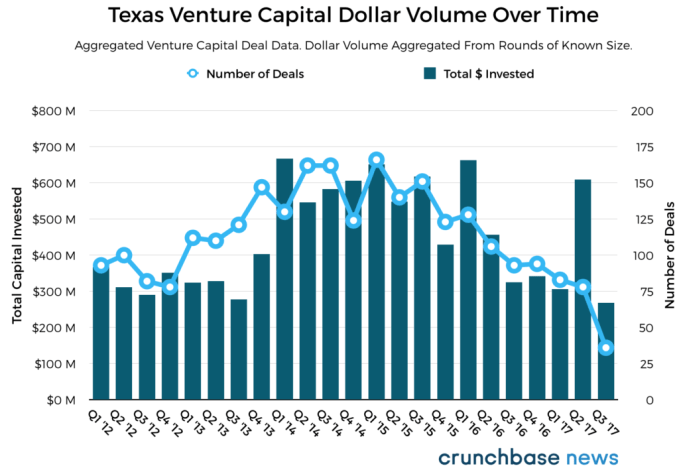

Readers of Mary Ann Azevedo’s report on the state of VC investment in Texas in Q3 2017 may remember the following chart:

It shows that, at the time of writing, the last full quarter of 2017 marks a multi-year low for both the number of venture capital deals and the amount of money raised in those deals. It was not the sort of chart to inspire hope for investors or founders.

But is Texas, the Lone Star State, alone? Or is this part of a broader pattern throughout the U.S.’s biggest VC funding markets?

Spoiler alert: It’s the latter, and for startups and investors, this could mean trouble.

We think there are two metrics that paint a bearish case for the U.S. startup market when examined over the nearly seven-year period between Q1 2012 and the end of Q3 2017: The total number of VC deals, which we’ll cover here. And in a forthcoming piece, we’ll look at the declining percentage share of VC dollar volume received by seed and early-stage startups.

A decline in overall deal volume

From the perspective of venture capital, there are two “first-order” metrics we could look at when assessing the overall health of the startup market in the U.S.: deal volume and dollar volume. Arguably, the number of deals is the better barometer, because, as we’ve seen recently, a small handful of outlier rounds — consisting of nine or 10-figure late-stage deals — can make it look like the whole market is swinging dramatically higher.

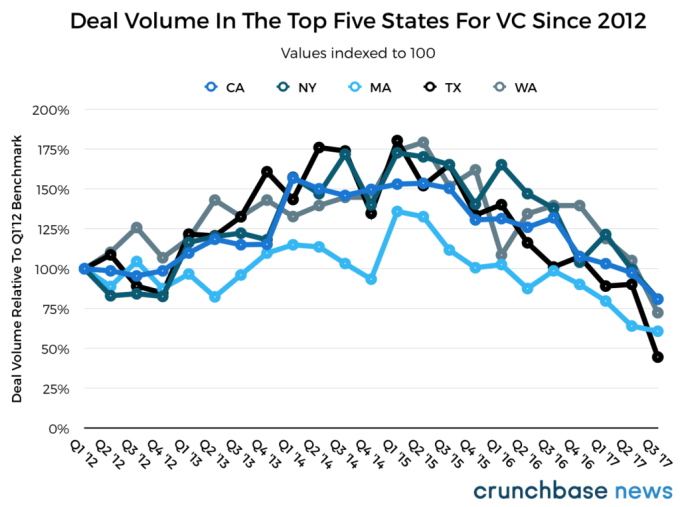

Turning back to Texas, Azevedo looked at investment activity in the Lone Star State’s startups from Q1 2012 onward. As it happens, Texas also is one of the top five states for startup deal volume during this period, so we decided to compare it against the other four: California, New York, Massachusetts and Washington. Collectively, these five states account for just over 65 percent of the more than 55,800 known venture deals struck with U.S.-based startups during the 2012 – Q3 2017 time period we analyzed.

Because there is a varying amount of VC activity in each state, and we wanted to compare deal volume in an apples-to-apples manner, we indexed each state’s deal data to a scale of 100 percent. In other words, we compare the number of deals each quarter against the number of deals listed in Q1 2012. (For a handy guide on indexing, the Dallas Federal Reserve has a very helpful resource.)

Here’s the chart:

All of the top-five markets by deal volume have seen a marked decline in the number of deals struck since hitting a local maximum somewhere around the beginning of 2015. That should feel directionally accurate. After all, 2014 was when Uber raised two massive rounds: a $1.4 billion Series D at a $17 billion valuation and, just six months later, a $1.2 billion Series E at a whopping $40 billion valuation. Those were heady days, indeed.

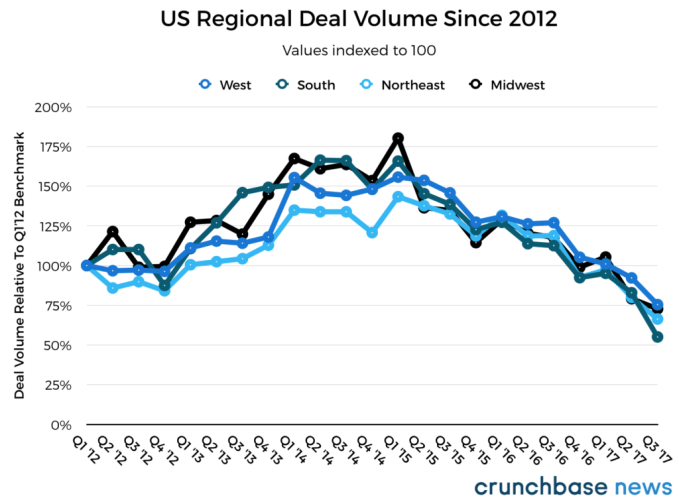

But, you might say, these are just the most significant markets. So what about the bigger picture? To address this, we aggregated 55,800 deals extracted from Crunchbase data by geographical region, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. We found a similar pattern:

As we saw in the former chart, a peak in deal volume at or around the beginning of 2015, as well as the tapering-off effect we saw in the case of individual states.

Even if we’re on flat ground, we still went down a hill

Granted, it’s entirely possible that this is because of sampling bias of some variety or another. Indeed, when making projections about VC activity, Crunchbase accounts for the fact that it can take a long time for information about certain deals (especially seed and angel deals) to make it into the database. The charts above use only reported data — deals that are already in the database — and as more deals get added over time, numbers will rise. But even in Crunchbase’s projections, which only go back to Q1 2013, projected U.S. deal volume for Q3 2017 is basically flat compared to when these projections started.

In other words, the U.S. VC market is more or less back to where it was six or seven years ago, at least as far as deal volume is concerned. So it means we’ve gone up a hill, peaked in Q1 2015 and moseyed our way back down the hill to at least flat ground and possibly a valley. We’ll see what happens in the following quarters.

The quiet passing of peak startup

Let’s return to what prompted our look at startup data through this lens: Jon Evans’s TechCrunch article from this past weekend. In it, he made an uncomfortably compelling case that peak startup has come and gone.

He suggests that because “we’ve all lived through back-to-back massive worldwide hardware revolutions — the growth of the internet, and the adoption of smartphones — we erroneously assume another one is around the corner, and once again, a few kids in a garage can write a little software to take advantage of it.”

The first wave of companies he cites, the Facebooks, Amazons and Airbnbs of the world, got big because the internet got big. The second wave — Snap, WhatsApp, Instagram, Uber — rode on the back of mobile’s rise to dominance.

The third wave? He observes, rightly, that VCs and the tech press like to talk a lot about AI, drones, self-driving cars, VR/AR and a whole slew of other whiz-bang technologies. But because there is no foreseeable path to widespread adoption (on the scale of everyone buying smartphones in the mid-2000s) because of the expense of building these systems and the short supply of talent, this third wave is, to slightly modify the title of a Cormac McCarthy novel, no country for young companies.

Market opportunities for new mobile and internet startups are fewer and further between. The “greenfield opportunities” MBA-types so often talk about have been mostly grazed over. The frontier? Dominated by giants. This cycle’s period of peak startup may have come and gone.

Featured Image: Li-Anne Dias