Thousands of major sites are taking silent anti-ad-blocking measures

It’s no secret that ad blockers are putting a dent in advertising-based business models on the web. This has produced a range of reactions, from relatively polite whitelisting asks (TechCrunch does this) to dynamic redeployment of ads to avoid blocking. A new study finds that nearly a third of the top 10,000 sites on the web are taking ad blocking countermeasures, many silent and highly sophisticated.

Seeing the uptick in anti-ad-blocking tech, University of Iowa and UC Riverside researchers decided to perform a closer scrutiny (PDF) of major sites than had previously been done. Earlier estimates, based largely on visible or obvious anti-ad-blocking means such as pop-ups or broken content, suggested that somewhere between 1 and 5 percent of popular sites were doing this — but the real number seems to be an order of magnitude higher.

The researchers visited thousands of sites multiple times, with and without ad-blocking software added to the browser. By comparing the final rendered code of the page for blocking browsers versus non-blocking browsers, they could see when pages changed content or noted the presence of a blocker, even if they didn’t notify the user.

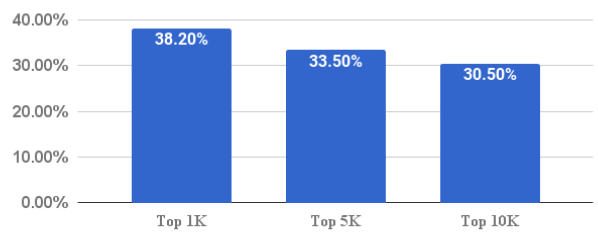

As you can see above, 30.5 percent of the top 10,000 sites on the web as measured by Alexa are using some sort of ad-blocker detection, and 38.2 percent of the top 1,000. (Again, TechCrunch is among these, but to my knowledge we just ask visitors to whitelist the site.)

As you can see above, 30.5 percent of the top 10,000 sites on the web as measured by Alexa are using some sort of ad-blocker detection, and 38.2 percent of the top 1,000. (Again, TechCrunch is among these, but to my knowledge we just ask visitors to whitelist the site.)

Our results show that anti-adblockers are much more pervasive than previously reported…our hypothesis is that a much larger fraction of websites than previously reported are “worried” about adblockers but many are not employing retaliatory actions against adblocking users yet.

It turns out that many ad providers are offering anti-blocking tech in the form of scripts that produce a variety of “bait” content that’s ad-like — for instance, images or elements named and tagged in such a way that they will trigger ad blockers, tipping the site off. The pattern of blocking, for instance not loading any divs marked “banner_ad” but loading images with “banner” in the description, further illuminates the type and depth of ad blocking being enforced by the browser.

Sites can simply record this for their own purposes (perhaps to gauge the necessity of responding) or redeploy ads in such a way that the detected ad blocker won’t catch.

In addition to detecting these new and increasingly common measures being taken by advertisers, the researchers suggest some ways that current ad blockers may be able to continue functioning as intended.

One way involves dynamically rewriting the JavaScript code that checks for a blocker, forcing it to think there is no blocker. However, this could break some sites that render as if there is no blocker when there actually is.

A second method identifies the “bait” content and fails to block it, making the site think there’s no blocker in the browser and therefore render ads as normal — except the real ads will be blocked.

That will, of course, provoke new and even more sophisticated measures by the advertisers, and so on. As the paper concludes:

To keep up the pressure on publishers and advertisers in the long term, we believe it is crucial that adblockers keep pace with anti-adblockers in the rapidly escalating technological arms race. Our work represents an important step in this direction.

The study has been submitted for consideration at the Network and Distributed Systems Security Symposium in February of 2018.

Featured Image: Bryce Durbin