Ubisoft combines AI research and game development at ‘La Forge’

When it comes to gaming, one usually thinks of “artificial intelligence” as somewhat less exalted than elsewhere; after all, for years we’ve been raging at cheating AI players, bemoaning their bad pathfinding, and laughing at their buggy antics. But AI can be and is being applied creatively, and those creative applications can lead to genuine scientific advances. Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest game publishers, aims to promote these mutually reinforcing goals with a new internal AI research unit it calls “La Forge.”

“Games drive innovation, and innovation drives games,” said Yves Jacquier, head of the La Forge project at Ubisoft Montreal (which turns 20 this year). “We started working with academics a while ago, as early as 2011, on how to combine AI with game ecosystem.”

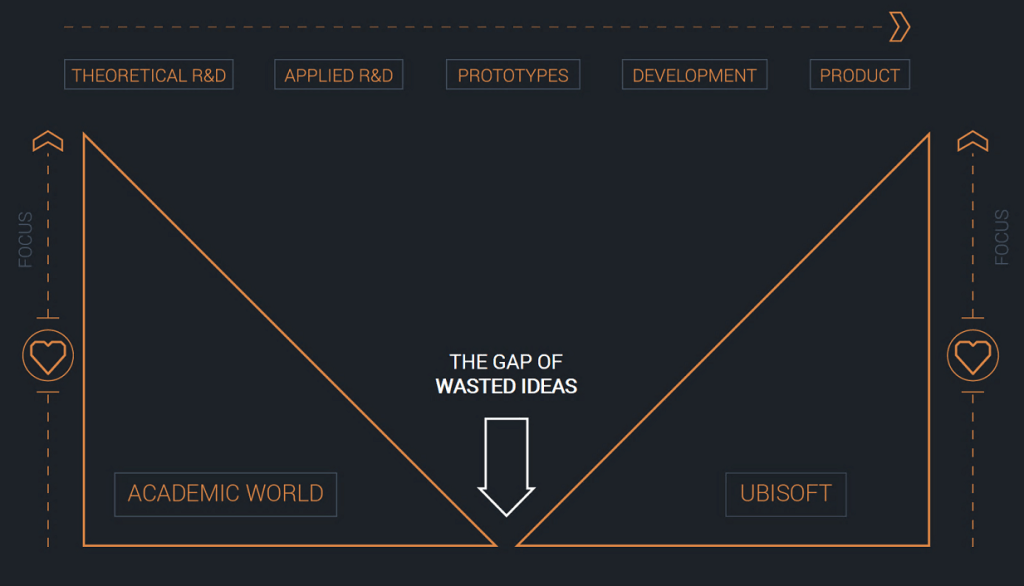

But these early efforts ran into a fundamental disconnect: academic people, obviously, need to publish, while Ubisoft’s researchers are incentivized to keep their advances inside the company. La Forge is the company’s attempt to bridge this gap.

People from universities and within the company were recruited “to create stuff with both scientific significance and marketable qualities,” Jacquier said. And lest you think this is just a forum or something (as I suspected at first), he then clarified: “It’s an actual space where Ubisoft employees and academic people, students, they come together and work on prototypes. They have all the resources any Ubisoft employee would have.”

Essentially, the bargain is this: Ubisoft provides reams of interesting data, and the researchers collaborate to do interesting things with that data; the former gets interesting new ways to manipulate that data, and the latter get to publish the interesting work they’ve done. It’s all very interesting.

Essentially, the bargain is this: Ubisoft provides reams of interesting data, and the researchers collaborate to do interesting things with that data; the former gets interesting new ways to manipulate that data, and the latter get to publish the interesting work they’ve done. It’s all very interesting.

Consider for instance the problem of autonomous cars. Ubisoft isn’t making one, but it has nevertheless created painstakingly detailed representations of real-world environments — such as the map of the Bay Area in Watch Dogs 2. These environments involve real-world physics, weather, even semi-autonomous pedestrians. Research here is fruitful for all parties.

“The objective with that was for us to find a better way, a more clever way to program the AI of the cars that we have,” Jacquier told me, for example creating realistic drivers of responsible, reckless, and cautious types. But researchers would also use it to test the possibilities of systems destined for the road, since a simulator like this is catnip for autonomous car developers.

“When you create this type of AI [i.e. a self-driving car] it’s difficult by nature to imagine how it would behave in all possible scenarios,” he said. “The idea is to use the engine to audit and create scenarios that you would not see in real life because it would be too difficult or unethical — involving pedestrians and so on.”

Testing in the real world is expensive and dangerous; doing quality control and experimentation with virtual sensor setups and other hardware is much easier to do virtually, as is setting up hazardous stress tests like navigating through a crowd.

Another place physical representations are useful is in ambulation; of course, physics-based movement has been tried many times in the past and is often glitchy and strange, though Disney Research published some promising work earlier this year. But here Ubisoft is once again at an advantage owing to its troves of data, in this case motion capture sessions.

Creating improved or more robust walking and running animations is of course beneficial to Ubisoft’s business, but how could that apply elsewhere?

“An example is trying to design prosthetics,” Jacquier pointed out. Fabricating and testing them in real life is once again a difficult and expensive proposition. Whereas, “if you have a real simulation of motion, you can design your virtual prosthetic and test it walking, falling, etc,” he said. This could help with the creation of prostheses that are custom-designed for someone’s body or gait but don’t require hours of testing or a series of uncomfortable prototypes.

The last example Jacquier gave is rather different: managing the toxic communities that seem to spring up around online games. “The game itself, that is something that you can master,” he said. “But the community is a beast.”

It’s also very data-heavy, making it potentially an ideal target for the kind of deep pattern recognition work that AIs are so good at. Recognizing toxic behavior or users before they become problems could go a long way to making online interactions less reliably awful. But gaming forums, while especially nasty, aren’t the only place this kind of thing pops up.

“Everything that had been learned for the gaming community is also applicable to schools,” Jacquier asserted. “All those behaviors that are happening, in terms of cyber intimidation and online bullying, are the same types of things you see in online communities.”

Ubisoft stands to gain from all this, of course, with improved tools and workflows. The company specializes in creating wide-open worlds that are somehow densely packed with detail, like flora, enemies, and structures — and it’s time-consuming to create these. Players notice instantly if the same tree or NPC is repeated or if two enemies use the same animation. AI can help there.

“It’s impossible to create a huge city where all the characters could be a main character — unless you have the tools,” said Jacquier. “The idea is really to help the people with an AI system that does the first 80 percent of the work and let them focus on the 20 percent that provides the ‘wow.’”

A few La Forge projects have been integrated into the company’s design tools, but the effort is still young.

“We started one and a half years ago with one employee, now we are working with six universities,” he said. “In parallel we have, I would say, 10 projects in the pipe, involving some 50 Ubisoft employees and 15 students.”

A major part of running a research unit like this, however, is publishing, which La Forge hasn’t done yet. But it’s on the way, Jacquier insisted.

“We are planning to publish. I can’t talk about them because they’re being submitted, but we have a couple examples already — talks at various conferences. Obviously we want to make sure that when someone is publishing something, we don’t want our unannounced games and stuff like that being publicized but we do think that being open, publishing, is a way to help us bring in leaders in the field.”

The attempt to merge private and academic research efforts seems to have met with early success in La Forge; it remains to be seen whether after a year or two the fruits of this labor will be compelling enough to keep the multidisciplinary team engaged. Keep an eye out for La Forge-associated papers at your friendly neighborhood AI conference.